Time in the Market vs. Timing the Market

The economy has held up better than many expected, but the longer that strength persists, the more investors rightfully start to wonder when the market breaks. For investors, that uncertainty often translates into hesitation: whether to stay fully invested, trim exposure, or wait for a pullback. It’s a natural impulse, especially when markets appear like they are about to collapse due to being bloated and overexpensive, and headlines reinforce the idea that a correction is overdue. But history shows that periods of discomfort are often when discipline matters the most. Time in the market has consistently proven more reliable than attempts to time it. That said, it’s worth putting today’s valuations in context – and that’s what we’re going to talk about in our article.

I received this text from a friend last week, and it captures a question that’s become increasingly common.

Whether in client meetings, market commentary, or financial headlines, there’s a growing sense of unease about where we sit in the current economic cycle. That concern isn’t misplaced. Markets have rallied meaningfully for the better part of two years, and valuations have risen alongside them.

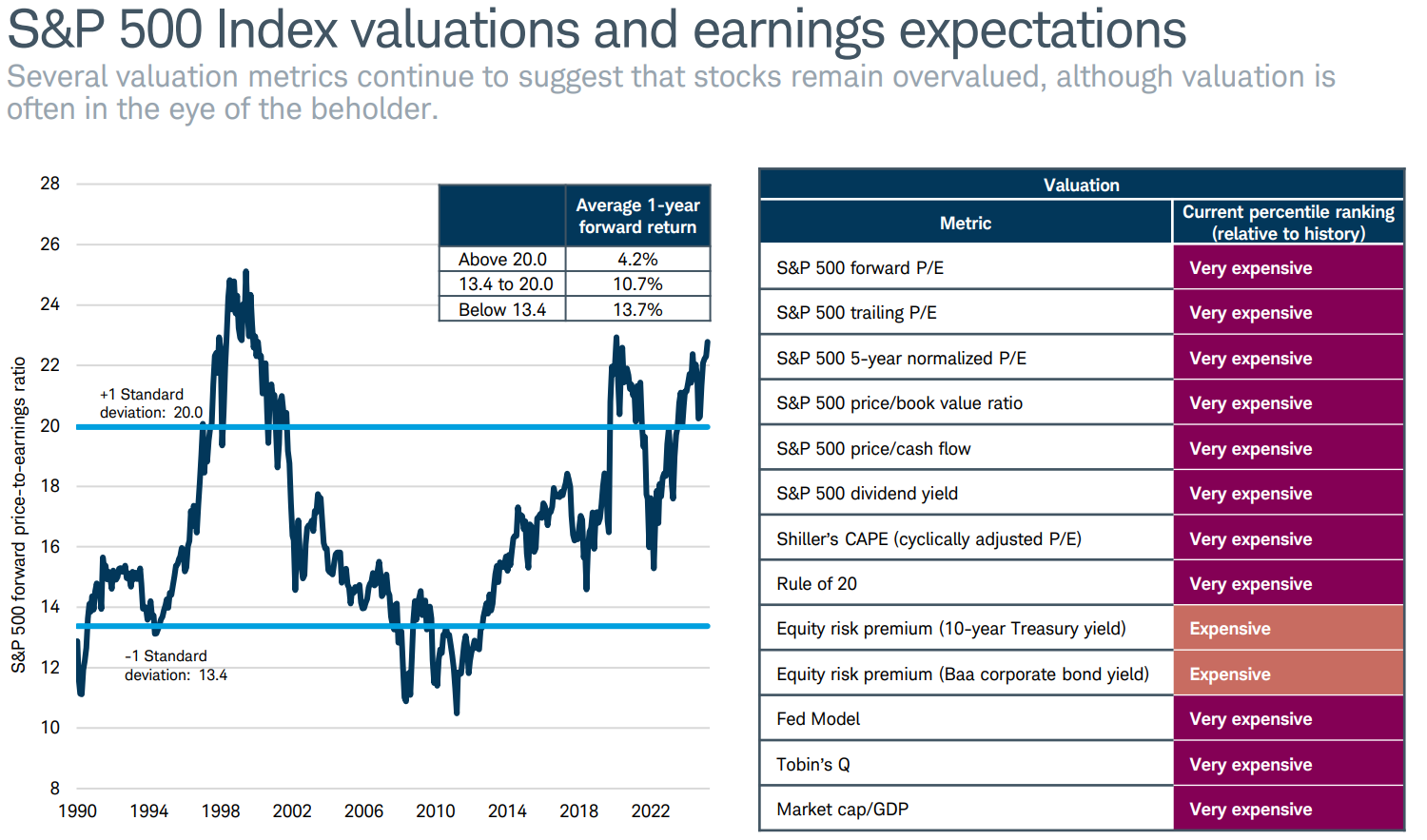

An expensive moment for US equities

The S&P 500 currently trades around 23 times forward earnings (23.23 as of 11/10 according to J.P. Morgan), compared with a long-term average of nearly 17 times. That’s elevated, but not unprecedented, and still below the extremes reached during the late-1990's tech bubble when forward multiples pushed past 25 times. Almost no matter what you look at, price-to-earnings, price-to-book, or Shiller CAPE ratio, valuations sit at the upper end of their historical ranges. By most definitions the U.S. equity market is “very expensive.”

Source: Schwab 2025 Q4 Quarterly Market Chartbook

Part of this reflects simple math: strong price performance over the past two years and resilient corporate earnings have kept valuation multiples high even as profit growth has somewhat slowed. According to J.P. Morgan, as of September 30th, the ten largest companies in the S&P 500 (Nvidia, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Broadcom, Meta, Tesla, and Berkshire Hathaway) accounted for roughly 40 percent of the index’s total market capitalization which is a record level of concentration. Much of that weight sits in firms tied to AI and digital infrastructure, sectors that have seen a surge in capital expenditures as companies race to secure computing power and data capacity. While those investments have supported earnings growth and equity performance, they’ve also raised concerns about sustainability and potential circular financing (although we’ll save that for another blog post).

Valuation – not a basis for investment decisions

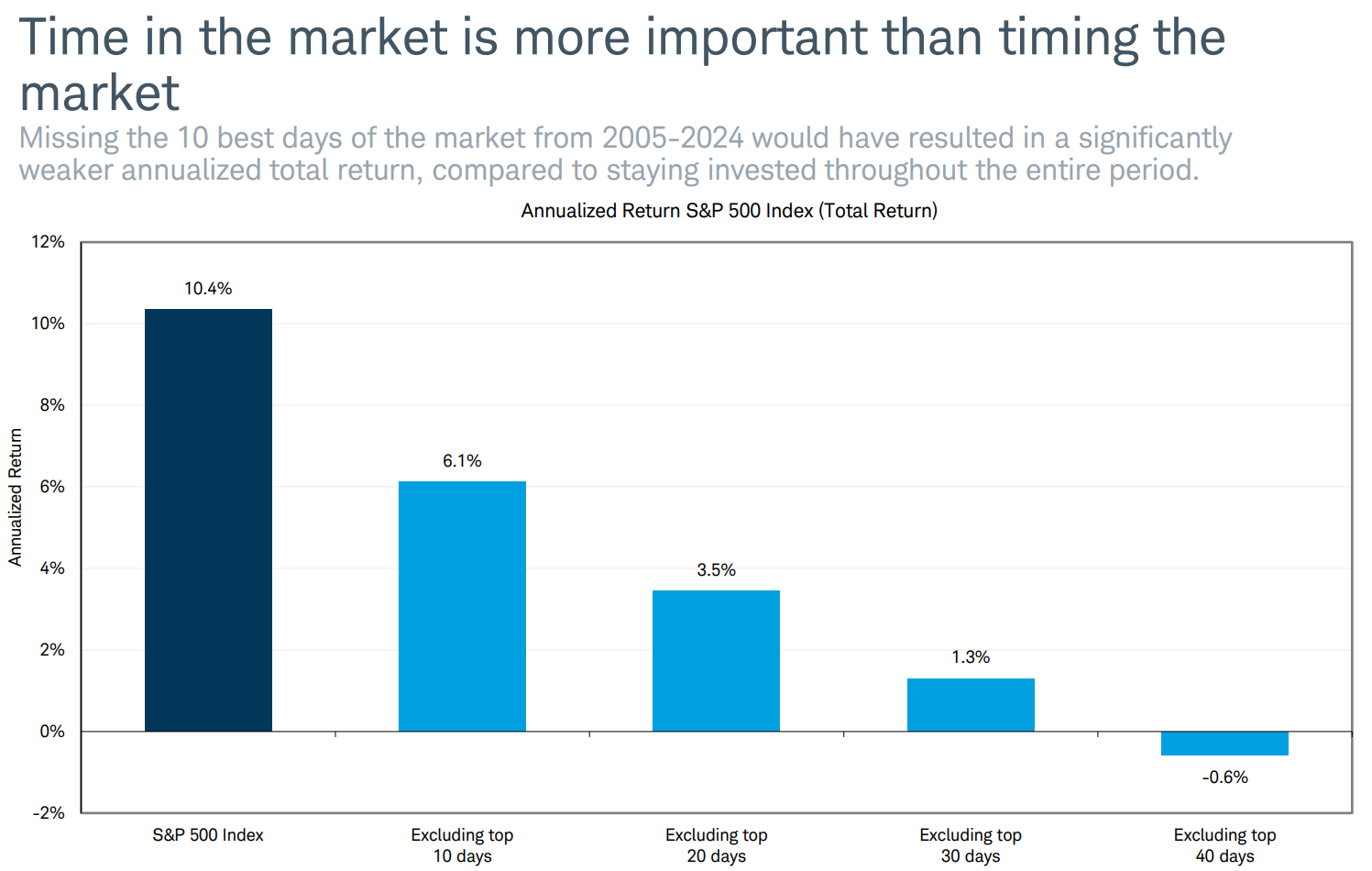

Valuations alone rarely provide much directional insight and have historically been poor market-timing tools. That distinction is important because volatile markets tend to create conditions where investors feel the most pressure to act. After strong performance, the natural question becomes whether it’s better to take profits, hold cash, or wait for a more attractive entry point. At face value, each of those options seems relatively reasonable. In practice, they typically lead to worse outcomes than simply staying invested.

Over the twenty-year period ending in 2024, an investor who remained fully invested in the S&P 500 earned an annualized return of roughly 10%. Missing only the ten best trading days would have cut that return almost in half to about 6%, and missing the twenty best days brought it down to roughly 3.5%. Those “best days” are impossible to predict and capture without continuous market exposure.

Source: Schwab Quarterly Chartbook

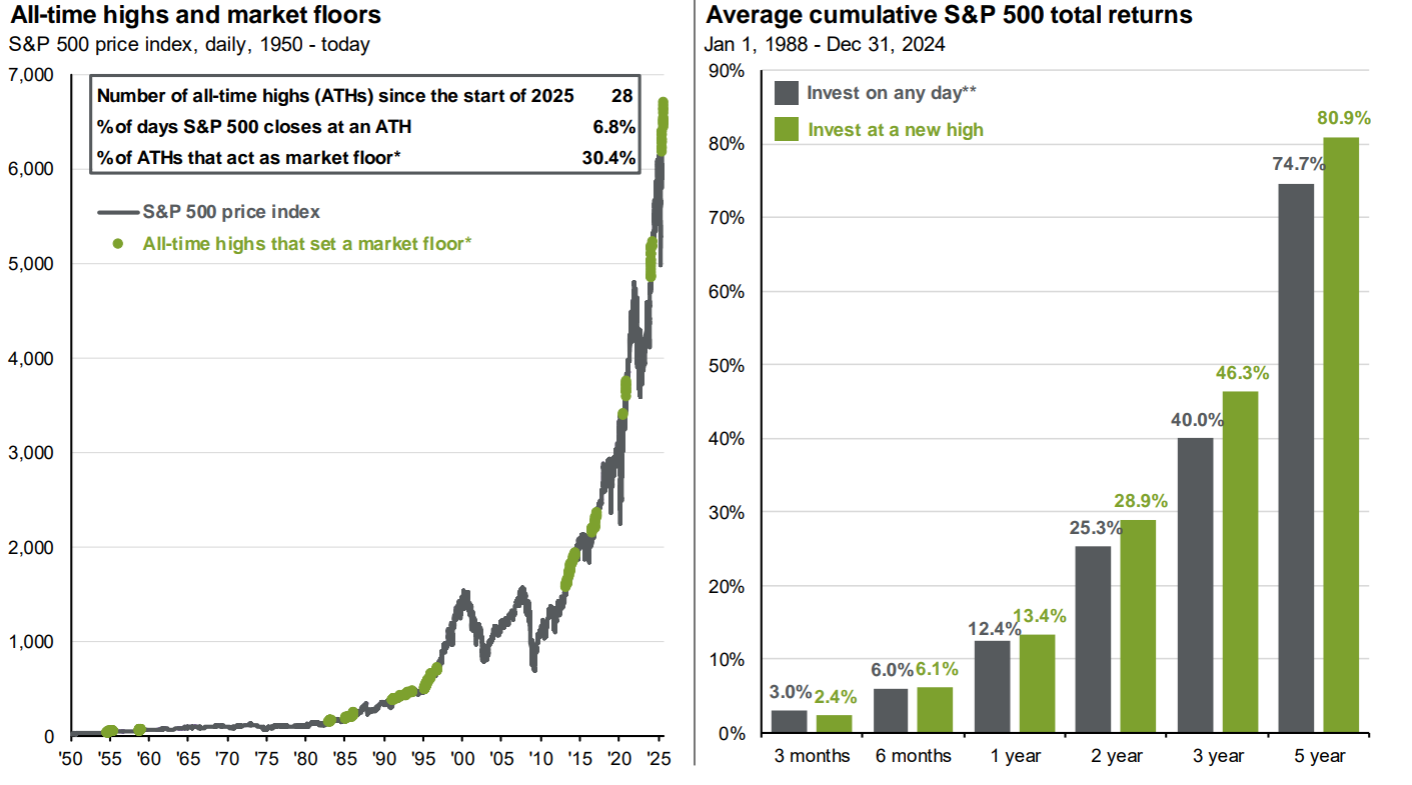

A similar story can be found when looking at market highs. Since 1950, returns following new all-time highs have been comparable to, and often stronger than, returns from random entry points. Roughly one-third of prior highs have ultimately marked new market floors rather than peaks. Waiting for the market to “cool off” has historically meant missing further compounding.

Source: J.P. Morgan 4th Quarter Guide to Markets

Now, this is all a lot easier said than done.

A young investor’s perspective on market crashes

As a 23-year-old, it’s even harder to relate to the fear and pain that comes with an extended bear market. I wasn’t around yet for the burst of the dot-com bubble in the early 2000’s, I was far too young to remember the great financial crisis, and although I was paying attention to markets during the COVID recession, it was far too short to understand what a drawn-out downturn actually feels like. That lack of experience cuts both ways.

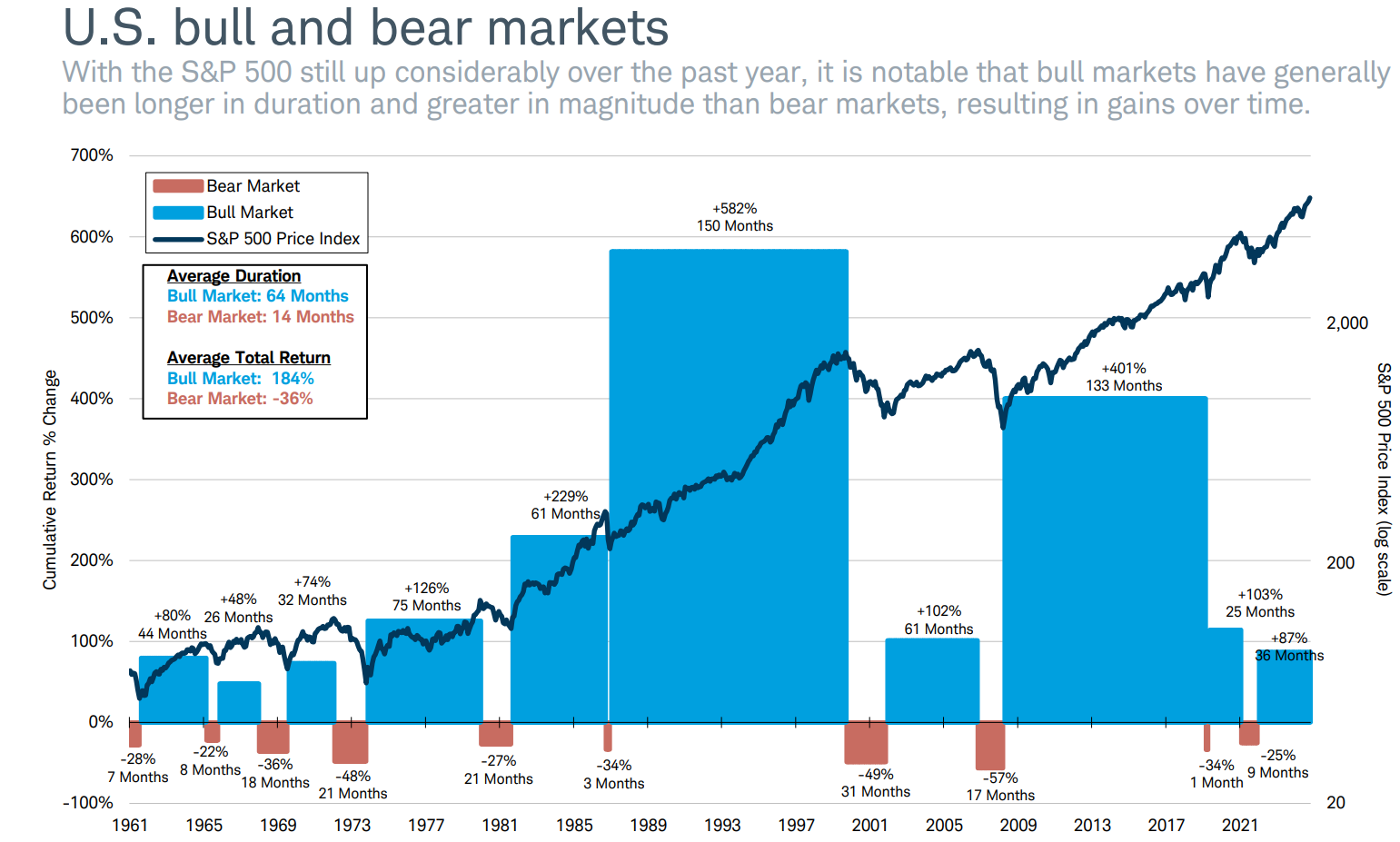

On the one hand, it makes it easier to stay optimistic, because most of what we’ve seen has reinforced the idea that markets recover quickly. On the other hand, it makes the thought of a drawn-out decline feel unfamiliar, and that uncertainty can be unsettling to say the least. It also comes at a time when many younger investors are just beginning to build savings, fund retirement accounts, and commit real capital to markets for the first time. Although it may not offer much comfort, bull markets typically last years, not months, and recover far more ground than the declines that precede them. But those recoveries only matter if you stay invested long enough to participate in them.

Source: Schwab Quarterly Chartbook

Cool-headed discipline wins

Periods like this can make even disciplined investors question their approach. When markets feel expensive and momentum driven, it’s natural to wonder whether optimism has gone too far or if we’re approaching the kind of excess that only looks obvious in hindsight. Nobody captured this notion better than Warren Buffett in his 2001 letter to shareholders:

“Nothing sedates rationality like large doses of effortless money. After a heady experience of that kind, normally sensible people drift into behavior akin to that of Cinderella at the ball. They know that overstaying the festivities—that is, continuing to speculate in companies that have gigantic valuations relative to the cash they are likely to generate in the future—will eventually bring on pumpkins and mice. But they nevertheless hate to miss a single minute of what is one helluva party. Therefore, the giddy participants all plan to leave just seconds before midnight. There’s a problem, though: they are dancing in a room in which the clocks have no hands.”

It’s a good reminder that process matters more than predictions, and that disciplined investing comes down to focusing on what you can control.

Conclusion

We are financial advisors in La Jolla, California. If you want to discuss your overall financial plan or retiring in California or other locations, please reach out to us and set up a time to talk.

Sources

JPMorgan Asset Management, Guide to the Markets® - US, September 30th, 2025, page 61

Charles Schwab Quarterly Chartbook Q4 2025

Connor MacKenzie is an Associate Portfolio Manager at Financial Alternatives. In his current position, he supports portfolio management, trading execution, and investment research, working closely with the firm’s partners to ensure client portfolios are managed with discipline and consistency.